In the December movie favorite, “A Christmas Story,” Ralphie and his friends cower in the presence of the neighborhood bully, Scut Farkus. That is, until one day when a snowball in the face provokes Ralphie to fight back and pound Scut into submission.

In the December movie favorite, “A Christmas Story,” Ralphie and his friends cower in the presence of the neighborhood bully, Scut Farkus. That is, until one day when a snowball in the face provokes Ralphie to fight back and pound Scut into submission.

Back in the 1940s, when the movie took place, bullying wasn’t hard to spot. It was physical, verbal and always overtly confrontational. That’s how we often think of bullying today, and in fact, whether it’s kids or adults, face-to-face confrontations are frequently the way bullies go after their prey.

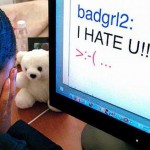

But it’s not the only way. Cyberbullying — through Internet social networks, texting and cell phones — can be as damaging as physical showdowns. And in some cases, it can be fatal, as demonstrated by the death of Phoebe Prince, a 15-year-old Massachusetts girl, who was targeted by classmates and hanged herself in January. The incident triggered widespread national publicity, reminiscent of other such incidents that have occurred and brought similar outrage and concern over cyberbullying.

Yet the practice continues and is likely to do so unless kids police themselves and their friends. But more importantly, parents need to take their heads out of the sand and realize that a Blackberry or laptop can become a weapon even in the hands of the most innocent-looking children.

With the power of the Internet and cell towers at their fingertips, kids who would never dream of shouting at another student or shaking a fist in someone’s face, can send threatening text messages or start vicious rumors on the Internet about another child. And they can do it with such a degree of anonymity that they can be difficult to trace. That is until there is a tragedy, which was the case with Phoebe Prince when authorities tracked down her tormentors and charged them with crimes in her death.

New York has a chance this session to take steps against such behavior with legislative proposals that have been introduced but have not passed in previous years to require school districts to establish policies against bullying and teach kids not to bully or cyberbully. The package of bills also requires reporting by district personnel of bullying incidents and establishes a statewide bullying hotline. Cost could be a factor with the initial price tag set at $53 million to implement such programs, but even if phased in over a few years, it’s a step the Legislature should take.

However, this is not just a legislative issue. The preventive steps that can avoid a Phoebe Prince tragedy can start at home with moms and dads talking to their kids, picking up on their conversations about other children, supervising their use of cell phones and the Internet and making sure that they become neither victims nor perpetrators of cyberbullying.

Some kids might find such intervention an invasion of privacy. Some parents might, too. But it’s like talking to children about drugs and alcohol. If you can save a kid’s life from ruin — your own or someone else’s — interceding is the right thing to do.